Source:

JOHNSON, G., and SCHOLES, K. (1997). Exploring Corporate Strategy, Fourth Edition, Prentice Hall, New York. [Chapter 8]

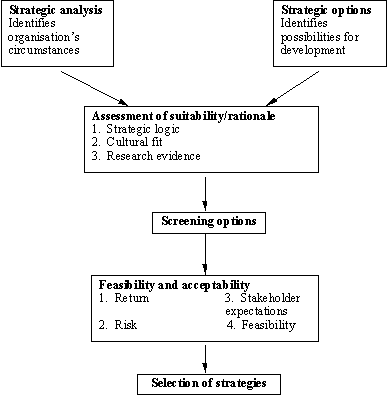

A useful way of looking at evaluation criteria is to view them as falling into three categories: suitability, feasibility, and acceptability.

Suitability:

One of the prime purposes of strategic analysis is to gain a clear understanding of the organisation and the environment in which it is operating. A simple summary of this situation might include a listing of the major opportunities and threats which face the organisation, its particular strengths and weaknesses, and any expectations which are an important influence on strategic choice.

Suitability is a criterion for assessing the extent to which a proposed strategy fits the situation identified in the strategic analysis, and how it would sustain or improve the competitive position of the organisation. Some authors have referred to this as ‘consistency’. Suitability can also be thought of as a ‘first round’ look at strategies, since many of the questions below are revisited in more detail when assessing the acceptability or feasibility of a strategy. Suitability is therefore a useful criterion for screening strategies.

The following questions need to be asked about strategic options:

- Does the strategy exploit the company strengths — such as providing work for skilled craftsmen — or environmental opportunities — for example, helping to establish the company in new growth sectors of the market.

- How far does the strategy overcome the difficulties identified in the strategic analysis (resource weaknesses and environmental threats)? For example, is the strategy likely to improve the organisation’s competitive standing, resolve the company’s liquidity problems, or decrease dependence on a particular supplier?

- Does it fit in with the organisation’s purposes? For example, would the strategy achieve profit targets or growth expectations, or would it retain control for an owner-manager?

Feasibility:

An assessment of the feasibility of any strategy is concerned with whether it can be implemented successfully. The scale of the proposed changes needs to be achievable in resource terms. Assessment will already have started during the identification of options and will continue through into the process of planning the details of implementation. However, at the evaluation stage there are a number of fundamental questions which need to be asked when assessing feasibility. For example:

- Can the strategy be funded?

- Is the organisation capable of performing to the required level (e.g., quality level, service level)?

- Can the necessary market position be achieved, and will the necessary marketing skills be available?

- Can competitive reactions be coped with?

- How will the organisation ensure that the required skills at both managerial and operative level are available?

- Will the technology (both product and process) be available to compete effectively?

- Can the necessary materials and services be obtained?

It is also important to consider all of these questions with respect to the timing of the required changes.

Acceptability:

Alongside suitability and feasibility is the third criterion, acceptability. This can be a difficult area, since acceptability is strongly related to people’s expectations, and therefore the issue of ‘acceptable to whom?’ requires the analysis to be thought through carefully. Some of the questions that will help identify the likely consequences of any strategy are as follows:

- What will be the financial performance of the company in profitability terms? The parallel in the public sector would be cost/benefit assessment.

- How will the financial risk (e.g., liquidity) change?

- What will be the effect on capital structure (e.g., gearing or share ownership)?

- Will any proposed changes be appropriate to the general expectations within the organisation (e.g., attitudes to greater levels of risks)?

- Will the function of any department, group or individual change significantly?

- Will the organisation’s relationship with outside stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, government, unions, customers) need to change?

- Will the strategy be acceptable in the organisation’s environment (e.g., will the local community accept higher levels of noise)?

Please reffer to the analysis of stakeholders and, in particular, stakeholder mapping. The way in which stakeholders ‘line up’ is dependent on the specific situation or the strategy under consideration. Stakeholder mapping is an important method for testing the acceptability of strategies. Clearly a new strategy is unlikely to be the ideal choice of all stakeholders. The evaluation of stakeholder expectations is therefore crucial.

A framework for evaluating strategies

Evaluating for Suitability

Strategic Logic, Cultural Fit, Research Evidence

(i) Strategic logic

The literature on strategy evaluation has been dominated since the 1950s by rational/economic assessments of strategic logic. These analyses are primarily concerned with matching specific strategic options with an organisation’s market situation and its relative strategic capabilities (or core competences). They attempt to establish a rationale as to why a particular type of strategy should improve the competitive advantage of the organisation.

Many analytical methods are useful both for understanding the current situation (strategic analysis) and for evaluating strategic options for the future. It is not the intention to provide a comprehensive treatment of all such analytical approaches, but rather to illustrate, through example, the different types of approach which might prove helpful in establishing the strategic logic, or rationale, behind a strategy. The following types of analysis will be discussed:

- Portfolio analysis — which help to assess how a new strategy might improve the balance or mix of activities in the organisation.

- Life cycle analyses — which assess whether a strategy is likely to be appropriate given the stage of the product life cycle and the relative strength of the organisation in its markets.

- Value system analyses — aimed at analysing how a strategic option might improve the performance of the value system as a whole. Assessment of synergy is a specific example of such an analysis.

The life cycle portfolio matrix

|

COMPETITIVE POSITION | Embryonic | Growth | Mature | Ageing |

| Dominant | Fast grow Start-up | Fast grow Attain cost leadership Renew Defend position | Defend position Attain cost leadership Renew Fast grow | Defend position Focus Renew Grow with industry |

| Strong | Start-up Differentiate Fast grow | Fast grow Catch-up Attain cost leadership Differentiate | Attain cost leadership Renew, focus Differentiate Grow with industry | Find niche Hold niche Hang-in Grow with industry Harvest |

| Favourable | Start-up Differentiate Focus Fast grow | Differentiate, focus Catch-up Grow with industry | Harvest, hand-in Find niche, hold niche renew, turnaround Differentiate, focus Grow with industry |

Retrench Turnaround |

| Tenable | Start-up Grow with industry Focus | Harvest, catch-up Hold niche, hang-in Find niche Turnaround Focus Grow with industry | Harvest Turnaround Find niche Retrench | Divest Retrench |

| Weak | Find niche Catch-up Grow with industry | Turnaround Retrench | Withdraw Divest | Withdraw |

Source: Arthur D. Little

Value System Analysis

The concept of synergy is concerned with assessing how much extra benefit can be obtained from providing linkages within the value system between activities which have either been previously unconnected or where the connection has been of a different type. Synergy can be sought in several circumstances, as is illustrated by the three strategies under consideration for a grocery retailer (See Figure 3).

- Market development (buying more shops) may improve performance in the value system, since it provides a further opportunity to exploit a good corporate image, and hence ‘launch costs’ are minimised compared with a new entrant. Buying power should also increase.

- Product development (into alcoholic drinks) would improve the use of a key resource (floor space), and cash is available to fund initial stock.

- Backward integration (into wholesaling) may well produce cost advantage if better stock planning can be achieved between the wholesale and retail partners.

Synergy could arise through many different types of link or interrelationship: for example, in the market (by exploiting brand name, sharing outlets, or pooling selling or promotional costs); in the company’s operations (by shared purchasing, facilities, maintenance, quality control, etc.); in product/process development (by sharing information/know-how).

Assesment of synergy for a grocery retailer

|

Degree of synergy with present activities | Strategy 1 Buy more shops | Strategy 2 Expand into alcoholic drink | Strategy 3 Open cash-and-carry wholesaler |

| 1.Use cash | Produces profit from idle cash | Produces profit from idle cash | Produces profit from idle cash |

| 2.Use of premises | None | More turnover/floor space | None |

| 3.Use of stock | Perhaps small gain from moving stock between shops | None | Reduction of stock in shops as quick delivery guaranteed |

| 4.Purchasing | Possible discounts for bulk | None | NoneReduced prices to shops |

| 5.Market image | Good name helps launch (i.e., cost of launch reduced) | None | Little |

Synergy is often used as the justification for diversification — particularly through acquisition or merger. It has been argued, firms which diversity by building on their core business do better than those who diversity in an unrelated way. However, this can be a difficult argument in practice for a number of reasons.

- The notion of a core business is not at all clear. Should it be defined by product or market or technology? It is often defined in terms of history, which can be misleading.

- A linked argument is that diversification may be more successful if it builds on core competencies. These may be related to technical skills or knowledge and seen as relatively transferable. On the other hand, core competencies can be regarded as much more linked to the ‘tacit knowledge’ and routines of the operation. In this sense, core competencies are more culturally based and are often difficult to transfer from one situation to another. This at least partly explains the difficulties that many organisations have had with diversification — assumptions are made about the transferability of core competencies when, in fact, they are not transferable.

- It has been argued that synergy should not be regarded as necessarily arising from horizontal linkages within the value system through the sharing of activities or skills, but can also arise from a shared strategic logic between businesses or business units. For example, in a conglomerate like Hanson plc the centre adds value not through managing interrelationships between its businesses but because its corporate systems and managerial competencies secure enhanced performances from a series of strategically similar subsidiaries.

Another area where value chain analysis can be useful to an assessment of the suitability of strategies is in the locational decisions of international companies. The logic of gaining competitive advantage through the management of individual value activities suggests that the separate activities of design, component production, assembly, and marketing may be optimally located in different countries. In consumer electronics, for example, design and component manufacture tends to be located in more advanced economies (e.g., Japan) while assembly is carried out in lower-wage economies (e.g., Korea, Taiwan). This needs to be balanced against the importance of well-managed linkages, which prove more difficult to achieve the more dispersed the separate activities become internationally. The most successful international companies are those which can develop organisational arrangements to exploit the advantages of specialisation and dispersion while managing linkages (or co-ordinating) successfully.

(ii) Cultural Fit

Although establishing the strategic logic of options is very valuable, it is also important to review those options within the political and cultural realities of the organisation. This section is concerned with how options might be assessed in terms of their cultural fit: in other words, the extent to which particular types of strategy might be more or less assimilated by an organisation. This is not to suggest that the culture of an organisation should have pre-eminence in determining strategy. Indeed, one of the key roles of the leadership of organisations is to shape and change culture to better fit with the preferred strategies.

These concerns are best understood in terms of the previous discussions about the cultural web of an organisation and how it legitimises and sustains the paradigm of the organisation. It is clear that, on the whole, organisations tend to adopt strategies which can be delivered without unduly challenging the paradigm — managers find such strategies easiest to comprehend and pursue. This is why the strategies of most organisations develop incrementally. However, the key judgment is whether or not such strategies are suitable for the organisation’s current situation — particularly if significant environmental change has occurred. The purpose of strategic logic analyses is to indicate whether or not the organisation’s paradigm requires some fundamental change.

Whether paradigm change is required or not, the assessment of strategic options in terms of cultural fit is valuable. If the organisation is developing within the current paradigm, these analyses help to identify those strategies which would be most easily assimilated. In contrast, if the paradigm will need to change, the analyses help in establishing the ways in which culture will need to adapt to embrace new types of strategy. This will be valuable when planning strategic change.

One of the key determinants of how culture might influence strategic choice is, again, the stage that an organisation has reached in its life cycle. Schein provides a useful discussion of the relationship between life cycle, culture, and strategy. (Four life-cycle stages are recognised: Embryonic, Growth, Maturity, and Decline. A number of cultural features are associated with each of these stages. For example, the Embryonic stage is associated with a cohesive culture in which the founders are dominant. In this stage, the organisation is usually not prepared to value outside help. Organisations in this stage tend to favour ‘related developments’. See Sections 7.5.1 – 7.5.4 from Johnson and Scholes, 1993.)

(iii) Research Evidence

The analyses in the previous sections have attempted to assess the suitability of strategies either by establishing the logic behind the strategy or through assessing the cultural fit. Since the major purpose of strategic change in most organistions relates to the need to sustain or improve performance, this section will review the research evidence which is available on the relationship between the choice of strategy and the performance of organisations. In this context the continuing work of the Strategic Planning Institute (SPI) through its PIMS data-bank is useful. This data-bank contains the experiences of some 3,000 businesses (both products and services). These are documented in terms of the actions taken by the business (i.e., its choice of strategic options), the characteristics of the market, competitive position, cost and investment structure, and the financial results. Some of the more important PIMS findings, together with other research, are summaried in this section.

Diversification and performance

Diversification is probably one of the most frequently researched areas of business. Much of this research has been undertaken within the ‘disciplines’ adjacent to strategic management (e.g., economics, finance, law, marketing). There have also been a number of research studies which specifically attempt to investigate the relationship between the choice of diversification as a strategy and the performance of the organisation in financial terms. Readers are encouraged to follow up the references for a full review of research findings on this topic.

Overall, it needs to be said that the various attempts to demonstrate the effects of diversification on performance are inconclusive. Research in the 1970s suggested that firms which developed through related diversification outperformed both those which remained specialised and those which developed through unrelated diversification. These findings were later questioned. The sum total of all of the research work linking patterns of diversification to financial performance is unclear apart from one important message: successful diversification is difficult to achieve in practice. Some of the specific findings of the various research studies are interesting:

- The concept of diversity should not be interpreted too narrowly as relatedness in product terms. Diversity is also an issue on other dimensions, such as market spread. There is some evidence that profitability does increase with diversity, but only up to the limit of complexity, beyond which this relationship reverses. This raises the issue of whether managers can cope with large, diverse organisations.

- The theoretical benefits of synergy through diversification are often difficult to achieve in practice. This is particularly supported in the research on diversification through acquisition. For example, Porter concludes in his study of 33 major corporations between 1950 and 1986 that more acquisitions were subsequently divested than retained, and that the net result was usually a dissipation of shareholder value and a company often left vulnerable to corporate raiders.

- An important conclusion of many research studies is that a universal prescription of the benefits of diversification is unlikely to be found. The success of diversification is extremely contingent on the circumstances of an organisation, such as the level of industry growth, market structures and the firm’s size. Some studies have also demonstrated that the relationship between performance and diversity will also vary with the period of time studied (e.g., the point in the business cycle). For example, related diversification might be more suited to firms when there are opportunities for expansion in a growing economy. On the other hand, in times of little or no growth a concentration on mainline products and/or seeking more market diversity might make more sense.

- Other studies argue that a key contingent factor is the resource situation of the organisation — particularly the existence of under-utilised resources. Slack in the physical resources or intangible resources (brand name, core skills, etc.) is therefore likely to encourage related developments, whereas excess financial resources may well be used to underwrite unrelated developments (e.g., through acquisition), particularly if the other resources are difficult to develop/grow quickly. This raises the question of whether successful performance is a result of choosing diversification or if the relationship is, in fact, the reverse. Perhaps successful organisations choose diversification if opportunities in their current product/market domain are limited.

Evaluating for Acceptability

Return, Risk, and Stakeholder Expectations

Return:

Profitability analyses (return on capital employed, payback period, discounted cash flow, earning potential, market valuation, etc.); Cost/benefit analysis; Shareholder value analysis.

Risk:

Financial ratio projections; Sensitivity analysis; Decision matrices; Simulation modelling; Heuristic models.

Stakeholder Expectations:

Needs, power, interest, and predictability of stakeholders.